.

This is the medieval section of StormTheCastle.com

- Knights

- Castles

- Games

- Weapons/Armor

- Articles

- Medieval Names

- Medieval Words

- Medieval Terms

- Medieval Jobs

- Medieval Maps

Wills Books

The Bad Fall of 1066...

Part II: The Battle of Fulford...

Part 2. The Battle of Fulford

By S. Jeffrey Duff © 2013

I. How King Harold and Anglo - Saxon England 'fell' into the Bad Fall of 1066

II. The First Crisis: The Battle of Fulford (September 20, 1066)

III. The Second Crisis: The Battle of Stamford Bridge (September 25, 1066)

IV. The Third and Very Final Crisis: The Battle of Hastings (October 15, 1066)

Chapter 1. Our Main Characters and the Impending Battle

As you will recall from the first chapter of our saga about the Year of Our Lord 1066, two-Anglo-Saxon earls were exhorted to prepare a defense by the new King of England, Harold Godwinson. Earl Edwin was the king’s appointed leader from the shire of Mercia, while his brother Morcar was the appointed Earl of Northumbria. Unfortunately for King Harold, Earl Edwin and Earl Morcar, they had all three become the sworn enemies of the king’s vindictive brother, Tostig Godwinson. Tostig was a man of decidedly mixed talents, but one of his talents was a violent temper and a strong thirst for revenge.

Tostig was the previous appointed Earl - similar to a territorial governor - of Northumbria. As Earl of Northumbria, Tostig had enforced the laws and taxation of the latest English King, a pious but passive man nicknamed Edward the Confessor. Unfortunately for peace - loving old King Edward, Tostig pursued the taxation of Northumbria with great and violent zeal, which benefitted himself, his friends and his agents in the shire. Oddly enough, Tostig’s relentless and forceful tax requisitions had made him a very unpopular governor among the 95% of Northumbrians who actually had to pay the king and Tostig’s taxes).

In October of 1065, the citizens of Northumbria had had more than enough of Earl Tostig. Being greedy, violent and unsympathetic to rich and poor alike, Earl Tostig had pushed Northumbria’s ‘thegns’ (basically, citizens with property) and peasants too far. During a brief journey outside Northumbria, the citizens rose up and replaced Tostig with a new earl; the Earl of Mercia’s brother, Morcar, was pushed willingly into the position of Earl. King Edward had mixed feelings about this usurpation, not liking most of the Godwinsons, but he chose Tostig’s older brother Harold to investigate and judge the situation. Rather surprisingly, Harold’s interviews in Northumbria caused him to advise King Edward that Northumbria –and Anglo - Saxon England- were better off with Morcar and much better off without Tostig. The King quickly agreed with Harold Godwinson and banished the infuriated Tostig from all of England.

As noted in Chapter 1, Tostig sought allies overseas and eventually latched on to the King of Norway, Harald Hardrada. With Tostig’s enthusiastic support, Harald had gathered a fleet of 300 Viking long ships, filled with about 10,000 experienced Viking warriors. Tostig Godwinson contributed a dozen more ships (most sailed by kidnapped English sailors) and some 400 to 500 followers and mercenaries from Scotland and Flanders. Tostig also supplied a large well of hatred for the people of Northumbria, the Earls Morcar and Edwin and, of course, the newly-crowned King of England, his older brother Harold Godwinson.

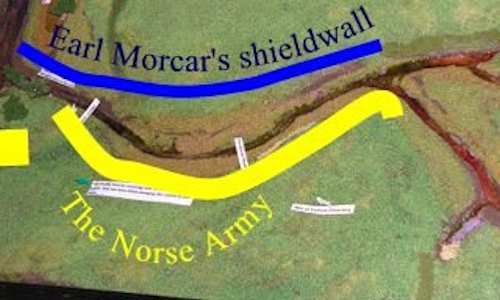

(Map courtesy of dismanibus156.wordpress.com)

The first action of King Harald and Tostig Godwinson were to sail up the Tyne River, thereupon to sack and burn the village of Scarborough. (Although Tostig desperately wanted to be reinstated to the lucrative and powerful position of Earl of Northumbria, it should be noted that he and his little band of mercenaries were enthusiastic participants in the looting and destruction of the harmless Northumbrian village of Scarborough.)

Next, Harald and Tostig sailed up the Humber River and ended at Riccall. Harald left about 3,000 Norwegian warriors and camp followers there, to guard the 300-plus Viking ships and their plunder from Scarborough. Thereupon, Harald, Tostig and about 7,500 men marched toward Yorkshire’s largest city, York. Harald chose York because it had once been controlled by the Vikings, although it had been returned to English sovereignty about 30 years before. Tostig chose York because this was his former capitol city, just a year before when he had been the Earl of Northumbria.

Meanwhile, the current Earls of Northumbria and Mercia had pulled together an army of 5,500 to 6,000 Men. Unlike Harald and Tostig’s 10,500 experienced (well, mostly experienced) warriors, the majority of this northern Anglo-Saxon army consisted of men who were normally farmers, bakers, herders, shopkeepers, etc. Only a thousand warriors – or less - were full-time men-at-arms, mostly from Northumbria and Mercia, but including the ‘small’ contingent from King Harold. These 1,000 (or fewer) professional soldiers, called “housecarls”, were expected to lead and fortify the 4,500 to 5,000 drafted, inexperienced militiamen (who were collectively called the ‘fyrd’).

Unfortunately for the Anglo-Saxons, Earl Morcar and Earl Edwin, were young men (and brothers) of ‘promise’, but they had little experience in leading men into battle. So, a mostly inexperienced English army was being led into battle by two inexperienced commanders. On the other side, a mostly experienced Viking army was being led into battle by two experienced war leaders, the King of Norway and the former Earl of Northumbria, Tostig Godwinson.

Remarkably, the two young English earls selected a very good defensive position, especially given their inexperienced army’s smaller size and relative inexperience in battle. The chosen battlefield was about 17 miles south of the City of York. The earls chose a boggy and slightly hilly piece of ground between the advancing army of invaders and the City of York. Just a couple of hundred feet south of the English army was a tidal estuary of the River Ouse, locally known as Germany Beck. South of the estuary was soggy, sloping ground and the two flanks of the English army were protected by the swirling tidal waters of the River Ouse and it’s small tributary, the ditch-like Germany Beck. This meant that Harald and Tostig’s 7,500 warriors would have to advance down a soggy, peat-covered hill, cross the shallow ford across the river – that ford being called Fulford by the locals – and then climb up a shallow hillside, in order to attack the 5,500 to 6,000 man army of the northern English. (The precise sizes of Middle Age armies were rarely accurate, so we can only guess at approximate participant and casualty numbers.)

As with most European armies of the time, both the Norwegian and English armies relied mostly upon foot soldiers and a battle tactic known as the ‘Shield Wall’. The typical foot soldier of the Middle Ages (at least, before 1200 a.d.e.), was armed with a spear, for ‘distant’ fighting, and axe or sword for close-up fighting and a circular (or occasionally tear-drop) shaped shield. When a well-disciplined army came together in a line of battle, each warrior would try to overlap his shield with the men to his right and left. When a large force was able to properly inter-lock their shields together, it would look like a long, unbroken line of shields – a ‘shield wall’. In the infantry battles of the era, the army that was able to batter their way through the opponent’s shield wall would almost always win the battle. (Once an army’s shield wall was penetrated or broken apart by an opponent army, its individual soldiers were much easier to wound or kill.)

(Courtesy of lead-adventure.de)

So, in the Battle at Fulford, Yorkshire, a mostly inexperienced English army would stand passively and force Harald and Tostig’s army to walk through a boggy field, cross the River Ouse at the ford, then re-form and attack uphill against the Anglo-Saxons’ waiting army and shield wall.

Given their army’s inexperience and smaller numbers (approximately 7,500 Vikings versus approximately 6,000 Anglo-Saxons), this was smart tactical thinking by the young earls. It forced the Vikings to march one to two hundred yards through wet bog land, cross a cold and fast-moving River at the ford, then reform their battle lines before crashing up the hill and into the English shieldwall. Given that tidal tributaries protected the two flanks of the northern English army and this was a tactically sound decision for the English army.

Unfortunately for the English, King Harald of Norway had seen a lot of shield walls in his life – and he had led dozens of Viking armies against defenders fighting behind shield walls. His greater experience in battle gave him tactical options that the English earls had never heard of.

Harald decided to use a trick originally made popular by the armies of the Byzantine Empire (the then-surviving remainder of the Eastern Empire of Rome). In addition, either Harald or Tostig remembered a thing or two about tidal estuaries that the Anglo-Saxon earls seem to have forgotten.

Chapter 2. A boring summer for both the Anglo-Saxon and Norman armies

Meanwhile, back on the Isle of Wight, King Harold and his army of about 9,500 housecarls and fyrd were getting tired of waiting for Duke William’s Norman invasion force. Possibly unnoticed by Harold was near-constant, Northerly winds. These winds apparently lasted most of the summer and early fall of 1066, holding William’s invasion fleet in its channel ports on the northern shores of Normandy (France). This same northern breeze had allowed King Harald Hadrada and Tostig Godwinson easy sailing from Norway to Scotland, then Scotland to the northeast English shire of York.

Chapter 3. The English Earls discover the Fickleness of Tides.

As of the early morning hours of September 15th, 1066, Earls Edwin and Morcar had decided to fight the Viking invaders in open combat. They had the option of placing their 6,000 (or so) soldiers behind the fortress walls of York, thereby forcing the Vikings to attack or besiege them. But, the earls were unsure of when King Harold’s army would be able to move north to Yorkshire, to relieve a siege of the city of York. Furthermore, if they had to be realistic about future events almost 200 miles away in Southern England, the earls knew that Harold and his army could be marching and fighting in that area against the Duke of Normandy's invasion army for weeks - even months! The city of York had not been prepared for an extended siege, so even several weeks in York could leave the city’s besieged defenders and citizens, starving and cold.

No, the Earls Edwin and Morcar saw open combat with King Harald’s Vikings army and Tostig Godwinson’s mercenary band as the best course to follow.

Edwin and Morcar marched their small army the 17 miles south of York, to a narrow-but-deep tidal tributary which branches off the River Ouse and runs generally east and west. Locally known as the Germany Beck, this tributary was more of a large ditch in appearance. But, at high tide, this ditch would fill with North Sea Salt water up to a man’s head or deeper. In addition to the Beck’s depth, include the thick silty mud at the bottom and a fast flow, and the Germany Beck was a dangerous obstacle to people, at high tide. (By the way, the Word Ouse is pronounced “ooze”, a hint at the condition of the River’s bottom.)

By using the rising waters in the Germany Beck, the Anglo-Saxons had found a formidable barrier to place between themselves and Harald and Tostig’s invading army. The only convenient ford across the River Ouse was the crossing known as the Fulford - under a shallow length of Germany Beck - and the earls’ English army was blocking the way past that ford.

King Harald had brought around 7,500 warriors up to road to York and he halted his army on the south side of Germany Beck, directly across the ford from the earls’ combined 6,000 man army. Harald was a very experienced warrior and he could see the wet bogland on either side of the fast flowing Germany Beck. Although the English army was only about 200-300 yards (or meters) away from his position, it would be a tiring slog for his men to attack the earls’ shield wall. King Hadrada knew whichever force went on the attack would be at a real disadvantage, perhaps equalizing his 7,500 experienced warriors in their battle against the Anglo-Saxon army’s 6,000 mostly inexperienced men. He could also predict that it would be to the English army’s advantage to stand fast on defense and force the Viking army to tire itself out on the offense, marching and fighting uphill upon boggy wetlands.

The Norwegian King had been a Viking warrior - and even.a paid mercenary - ever since he was a teenager. He had raided and battled from northern Europe to southern Europe, from Ireland in the west to Russia and Byzantium in the east. To be more specific, Harald had a couple of tricks to use on the English army, tricks that would greatly improve his army’s odds for winning the upcoming battle. Tricks that Edwin and Morcar had never thought of, in their inexperience.

(Courtesy: fulfordbattle.com)

With no need (or desire) for haste, the King selected out about a third of his army and ordered them to move left into and behind a large stand of trees. This was to be his elite assault force, almost 2,500 of his best Viking warriors, who were to stay hidden and quiet until Harald gave them new orders, later. By mid-morning, Harald’s hidden assault force was in place and the remaining 5,000 warriors and mercenaries had moved forward and were lined up in battle formation, just across Germany Beck from the English army, less than 200 yards/meters away.

As was common in medieval warfare, the two armies began banging their shields and yelling taunts and curses at each other. Observing carefully, King Harald could see no sign that the English were going to cross the ford (‘fulford’) and attack his own army, despite there being only about 5,000 warriors in view of the English. Harald wasn’t surprised and calmly ordered his chieftains -- plus Tostig Godwinson-- to proceed with their frontal attack on the Anglo-Saxons shield wall.

The 5,000 Vikings - including Tostig’s band of 500 mercenaries - charged down their shallow hill and splashed through the cold seawater of the Germany Beck ford. When the last warriors climbed onto the north bank of Fulford crossing, they again formed themselves into a line of battle and started trudging up the Saxon’s soggy hillside, screaming oaths and banging their round shields with their battle axes and swords.

Meanwhile, the Earls of Mercia and Northumbria had chosen not to order their men to charge down the hill, which would allow their warriors to attack the Viking army while it was crossing the ford and therefore be partly disorganized. This shows how inexperienced most of the English army was, that the earls could not march them down to the ford to attack the Vikings at an advantage, at the water’s edge. Frankly, Edwin and Morcar were expecting that their army would become hopelessly disorganized in the melee, which would devolve into a mass of individuals fighting their enemies one-on-one, where the advantage would definitely be enjoyed by the army with the most experienced warriors - namely, the Vikings. The earls decided to keep their men lined up on their shallow hilltop, where their flanks would both be completely protected by the deep, dangerous tidal waters of the Germany Beck and the RIver Ouse.

Edwin stood behind his smaller Mercian force on the right wing of the English shieldwall. Morcar stood just behind his larger Northumbrian force, on the left and center of the same shieldwall.

-resized.jpg)

(Courtesy: samuraidave.wordpress.com)

As described by an English warrior later, the two sides crashed into each other with “a sound as loud as thunder.” The 6,000 men of the English shieldwall were fresh and ready, while the 5,000 men that the King of Norway sent across the ford were more battle-hardened, but suffering some fatigue from walking through the cold for waters and marching almost 200 yards (meters) through spongy, muddy bogland. The two walls of shields, plus the rows of men behind the front row shield men, now pushed back and forth. The men on both sides were yelling, cursing and screaming at each other. While pushing at the opponent’s shields with one arm in their own round shield, thousands of men were using their other arm - usually their right arm - to swing their battle axes and swords against the enemy warriors opposite from them. This was medieval warfare at it’s most old-fashioned, bloody and brutal. (The ancient Persian, Greek and Roman armies would have been quite familiar with the battle tactics at Fulford, showing how little warfare had changed in over 1,500 years.)

After two or three hours of this hand-to-hand fighting, the historical records reflect that the Anglo-Saxon army (6,000 men) was actually driving the smaller Viking force (5,000 to 5,500 men) back down the marshy hill, towards the Fulford. Both sides had lost many men, but the English were doing surprisingly well against the more experienced Vikings - plus Tostig’s Flemish and Scottish mercenaries.

King Harald was still on the other side of the ford, except he had moved to his left and joined his 2,000 to 2,500 Vikings hiding in the woods. Every so often, he had ordered one of his warriors to set down his shield and weapons, then try to cross through the deeper section of Germany Beck, that flowed in front of the forest and between his force and the on-going battle. Each time, the warrior had nearly been swept away and could not reach the other side of the ditch. Harald continuously watched the battle, which was only about 75 - 100 yards away from he his small assault force, while the King also kept a close watch on the depth of the Germany Beck’s water level. When he saw that the Viking shield wall was starting to be pushed backwards, back down the hill from the shield walls’ first thunderous collision, Haralda ordered another of his warriors to again try to cross the Germany Beck, to the English side of the ditch. This time, due to the tidal waters starting to flow out of the ditch, into the River Ouse and then back into the North Sea, this unnamed Viking warrior was able to walk to the other side without using the ford.

This was the confluence of events that King Harald had been waiting for, since three hours before! The English army was slowly pushing the the understrength Viking and mercenary shield wall back down the hill, towards the Germany Beck. As used for centuries by the Byzantine army, the experienced war leader saw that the advancing English army had now exposed it’s right flank (i.e., it’s right end) to a devastating flank attack by Harald’s hidden force! In addition, the tide had turned in the mid - afternoon and both the River Ouse and Germany Beck were steadily lowering their depths with the outgoing sea tide!

Chapter 4. What the Tides giveth, the Tides can taketh away.

In the heat of this long and bloody battle, Earls Edwin and Morcar had forgotten to keep a watch on the tides and water depths of the River Ouse and it’s tiny tributary, German Beck. They were counting on the deep, flowing cold water of the Germany Beck to protect both their left and right flanks. But, as the day’s carnage and chaos continued, it was understandable that Edwin and Morcar would fail to notice that the tidal waters of River Ouse and Germany Beck had started to lower, as they had every day, since the last Ice Age. In military parlance, their flanks were now “up in the air”... their flanks were wide open and no longer protected by deep, cold sea water.

The two young earls may have forgotten about the importance of the English flanks, but the old warlord Harald Hardrada had kept them firmly at the front of his mind. When the King of Norway saw his chosen warrior standing safely on the opposing shore of Germany Beck, Harald ordered his 2,000+ crack Viking warriors to come to the water’s edge. Then he and his warriors crossed the belly - high seawater to the north shore. He briefly gathered up his warriors, then charged against the very end - and the rear - of the English shield wall’s right flank.

The English right flank had little or no warning of King Harald’s sneak attack and neither had their nearest leader, Earl Edwin of Mercia. The Vikings smashed into the Mercian right flank with blood-curdling cries, and some of the right flank’s Anglo - Saxon warriors tried gamely to turn to their right and engage Harald’s assault force. It was too little, too late, and most of the other Mercian warriors simply turned and fled. Edwing fled to his left also, reportedly to warn his brother Morcar who was behind the center of the English shieldwall. Before Morcar was able to respond to Edwin’s warning, the Viking Berserkers were upon them and the Northumbrian warriors in the center.

Thereupon, the English center quickly fell apart and began a hasty retreat to their left. The Northumbrians on the left wing had only a few seconds of warning, then they too started to fall apart and retreat. As the Viking Berserkers charged along the rear of the English line, from it’s right wing to it’s left wing, some Anglo-Saxon warriors began retreating in all directions, trying to escape the enemy warriors to their front, their right and their rear. This meant that the English ran mostly to their left, which forced them to cross another section of the receding Germany Beck while under vicious attack by the Vikings and Tostig’s mercenaries.

If the Germany Beck and River Ouse were still near their tidal peak, at the time of the English retreat, the Anglo-Saxon army would have been totally annihilated by weapon wounds and drowning.

Fortunately for the English, the Germany Beck’s depth was only about thigh high, so most of the retreating warriors were able to avoid death by drowning. Unfortunately for the Anglo-Saxon army, thousands of Vikings and mercenaries were chasing them from close behind, with swords and axes swinging, The English army was routed, but not annihilated, although no clear casualty figures were ever available. We do know that a Viking writer stated that after the battle was over, the Vikings could walk across the Germany Beck and the Anglo-Saxon dead were so thick that the norsemen never got their feet wet.

Ironically, despite the widespread carnage and injuries on both sides, the four major leaders were not significantly wounded at the Battle of Fulford. The Anglo-Saxon army suffered at least a thousand dead (possibly to 1,500), most of whom were killed during the English army’s sudden collapse and retreat. The number of English wounded is unknown, but their army’s surviving soldiers were scattered to the hills and gone.

King Harold’s loyal Earls of Mercia and Northumbria were to play no significant part in the two upcoming battles - at Stamford Bridge and Hastings - nor were the 4,500 to 5,000 badly-shaken English warriors who survived the Battle of Fulford.

The Norwegian Viking army - and Tostig Godwinson’s small battalion of mercenaries - combined to suffer probably 500 to 700 battle deaths (again,the Vikings actual death count was never written down), at what became known much later as the Battle of Fulford. Norwegian King Harald Hadrada and Tostig Godwinson survived this battle without any injuries.

The invaders had suffered about half the number of casualties as the defending Anglo-Saxon army and the Viking army was the Master of the battlefield. But, at least as important, the norsemen had widely scattered the northern English army and it could not be reorganized and reconstituted in time to help King Harold in the future battles at Stamford Bridge and Hastings.

The Battle of Fulford had been a defeat for King Harold Godwinson of England and he would learn that fact within a couple of days. But King Harold would not see the full damage done to Anglo-Saxon England on September 20th, at the Battle of Fulford. The real harm to Anglo-Saxon England would be seen on October 15th, 1066, at the more famous Battle of Hastings.

Continue on to Part 3, ‘The Battle of Stamford Bridge’ ...

Some Medieval Items on Amazon for you

These are affiliate links, Will makes a small percentage of the sale

I have picked some best sellers for you

King Arthur Medeival short sword dagger - Medieval Chainmail Coif - DaVinci's Battalion