Mediaeval iron work furnishes material that is particularly interesting in a study of tool-wrought ornament. The use of iron as a strong factor in art properly begins with the period of mediaeval history. The ancients used iron ; but the material occupied a subordinate place in their work. With the beginning of mediaeval history the blacksmith enters upon the scene as an artisan of the first importance ; in no other craft can one trace more clearly the significant influence of the tool in shaping forms and patterns, — a beauty that was achieved upon a background of generation after generation of tool-trained men. Iron would seem to be the last material to which a man would turn for beauty's sake alone. Its associations have generally been with stern necessity ; its forms have almost invariably been those that utility has demanded for strength and resistance. To other materials more easily worked, or of greater intrinsic value and inherent beauty, such as ivory, gold, silver, enamel, or wood, the craftsman has turned for forms of convenience and luxury. But iron, the least promising material of all in its crude state, has generally come to the hands of the man who must build as utility points the way. More credit to the blacksmith that, through the distinction which comes from fine craftsmanship alone, he should rise head and shoulders above the purely useful trades and place his work beside that of the goldsmiths and silversmiths as a product possessing the highest order of beauty.

Consider for a moment the form in which the iron was delivered at the forge of the mediaeval smithy. The ore was smelted by simple processes at the mines back in the forests or on the mountain sides, rudely formed into ingots of such size that they might be easily transported, and brought to the towns to be bartered in trade. To-day the iron may be purchased in a great variety of forms, rolled into sheets of any desired thickness or into bars and rods, round, square, octagonal, of such lengths or dimensions as the worker may specify. But the early smith started, perforce, with the rough ingot, beating it out with the most arduous kind of manual labor into forms adapted to his purpose. Nothing could be more unsuggestive than the raw material left beside his forge. To win from it a straight, flat bar suitable for a hinge was in itself a difficult task. Persistently stubborn and resistant, it could be overcome only during the brief interval after it was pulled sputtering hot from the fire. Then back to the fire it must go again to bring it to a workable condition. There was no coaxing with light taps, no " correction to righteousness " ; each blow must needs be forceful, direct.

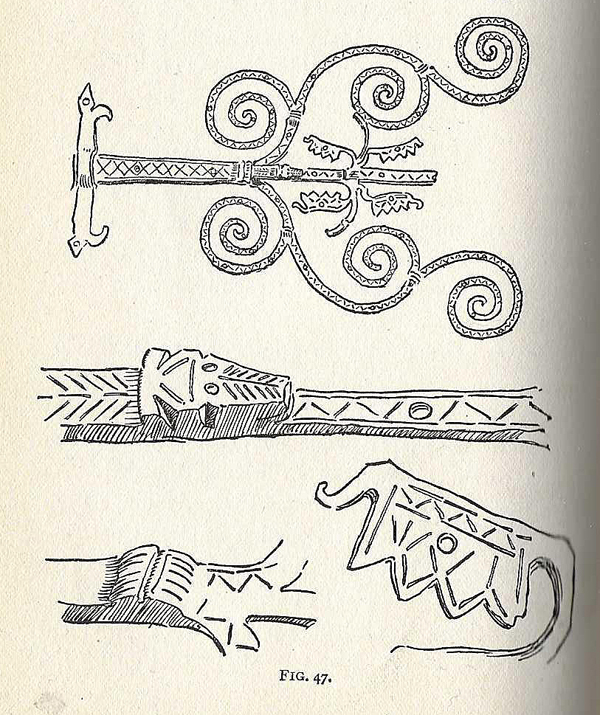

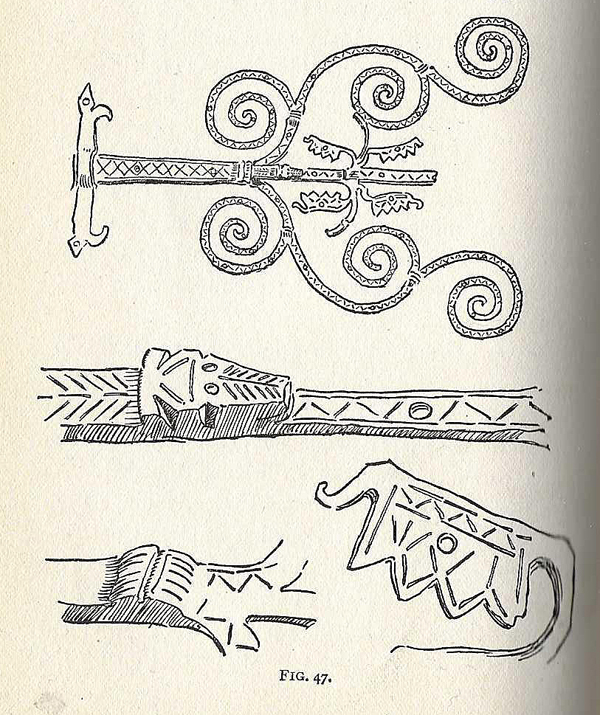

The worker started with a forge, an anvil, two or three hammers and chisels, a punch, and similar tools of the simplest contrivance. The material, as we have seen, must be shaped while hot; and while in this state separate pieces may be welded together. As work typical of these conditions the early hinge from St. Albans, Figure 47, is a good example.

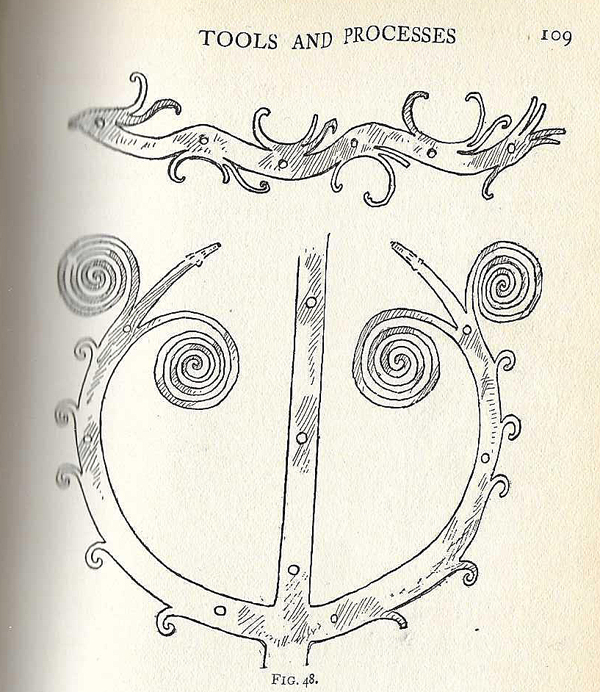

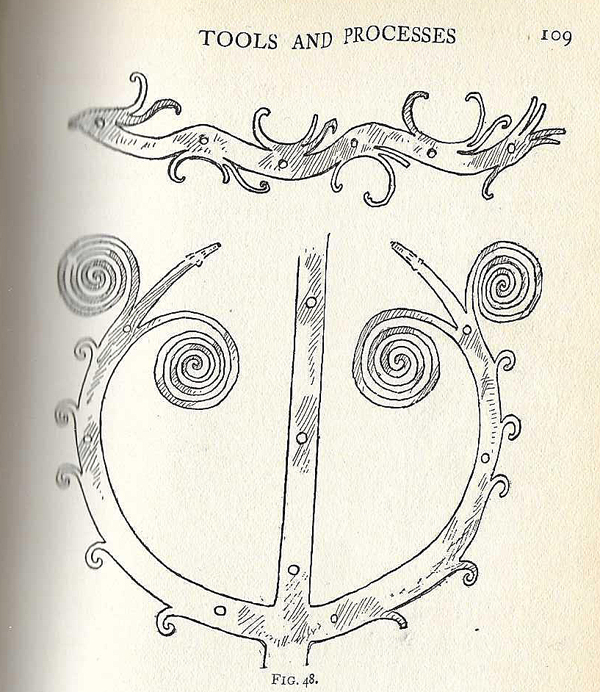

Constructively, the hinge had to spread out over the surface of the door to bind the planks together and secure a firm clutch for the service it had to perform. It was bolted through the door to plates or straps of iron on the inside. In this hinge one may readily note the character that came from the processes employed, and in all of the details the tracks of the tools are plainly indicated. The rudely formed head in the enlarged details is nicked and scarred with chisels ; the welding points of the various pieces are enriched in a similar way ; the surface of the hinge is cut with a simple zigzag pattern. It possesses that organic, intimate, personal quality which none but a tool-trained man could achieve. It is iron, — and looks like iron. In Figure 48 are other typical bits of tool-made ornament, literally split off with the chisel and hammer.

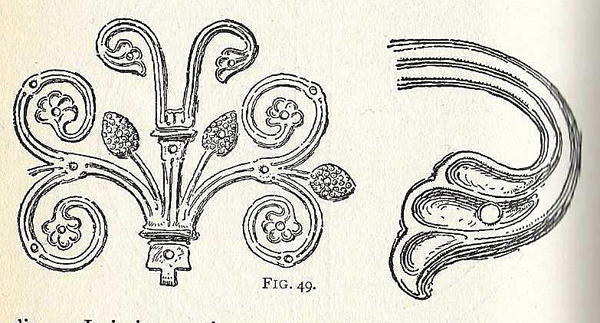

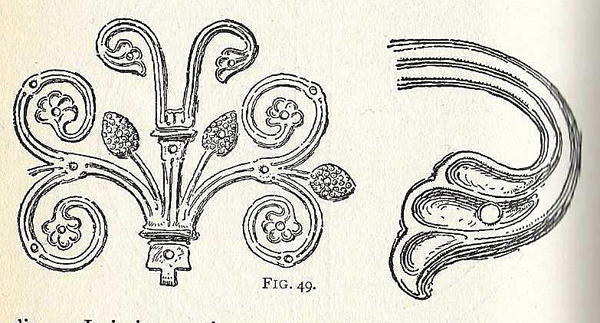

During a period of about two centuries simple, forged ornament of this type continued to be made. In France some ingenious smith devised a method of working that brought a note of variety to the flat treatment generally followed, as may be seen in Figure 49 and Plate 16.

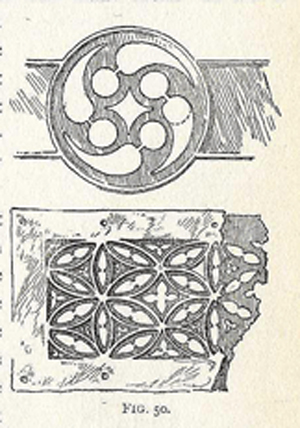

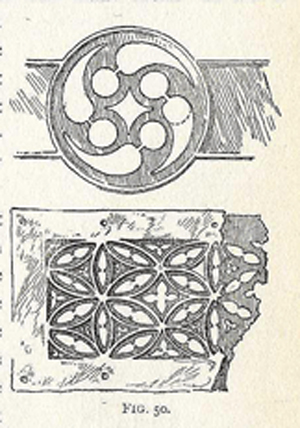

The terminating ends were gained by beating the hot metal into swage blocks or dies. It is interesting to trace the wanderings of some craftsman familiar with this method of working into other lands, and the efforts to imitate the work by others unfamiliar with the process. The term journeyman worker had a real meaning in those days. Through his handiwork a man established a reputation, and he was often sent for from distant points, followed in the wake of conquest or journeyed on peaceful mission bent, from one town to another. This peculiar type of work offered additional possibilities, culminating in the wonderful hinges of Notre Dame of Paris, beyond which there seemed no skill to venture. Nothing could serve as a better illustration of the fact that beauty entered into daily work than that these masterly hinges were generally credited to the devil for lack of definite knowledge as to who made them. It was a time when workmen in every craft were capable of rising to the finest achievements in the most unassuming way whenever the opportunity occurred.  Into the worker's kit there came in due season other tools, such as the drill and file ; and here again we may follow the trail left by these tools through innumerable examples of openwork ornament leading to forms of leafage and intricate traceried patterns. Working on the cold metal was more generally practiced, and the character of the enrichment accordingly underwent a change. The traceried patterns, suggested presumably by the masons, were of rare beauty, often complicated in appearance and of ingenious workmanship (Figure 50). Into the worker's kit there came in due season other tools, such as the drill and file ; and here again we may follow the trail left by these tools through innumerable examples of openwork ornament leading to forms of leafage and intricate traceried patterns. Working on the cold metal was more generally practiced, and the character of the enrichment accordingly underwent a change. The traceried patterns, suggested presumably by the masons, were of rare beauty, often complicated in appearance and of ingenious workmanship (Figure 50).

Plant forms first appear in an abstract way, gradually developing into more specific forms. The worker, with increasing skill and better appliances, turned, as does every designer sooner or later, to Nature for assistance.

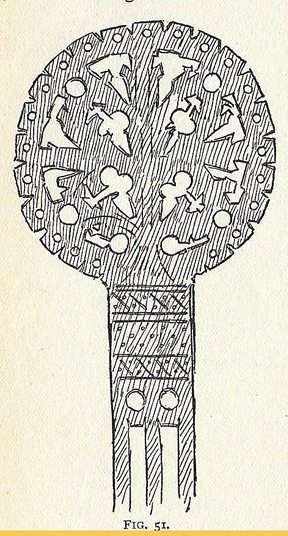

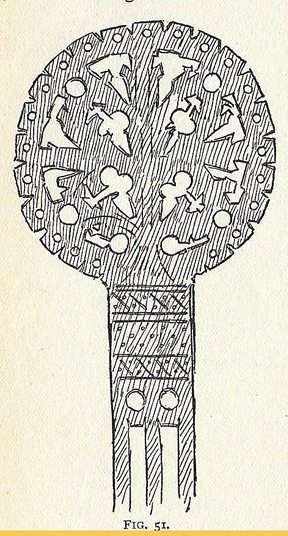

In Figure 51 is a very abstract sort of leafage, just the thing that a workman with punch and cold chisel would shape from a flat piece of metal ; it is tool-made Nature. In Figure 51 is a very abstract sort of leafage, just the thing that a workman with punch and cold chisel would shape from a flat piece of metal ; it is tool-made Nature.

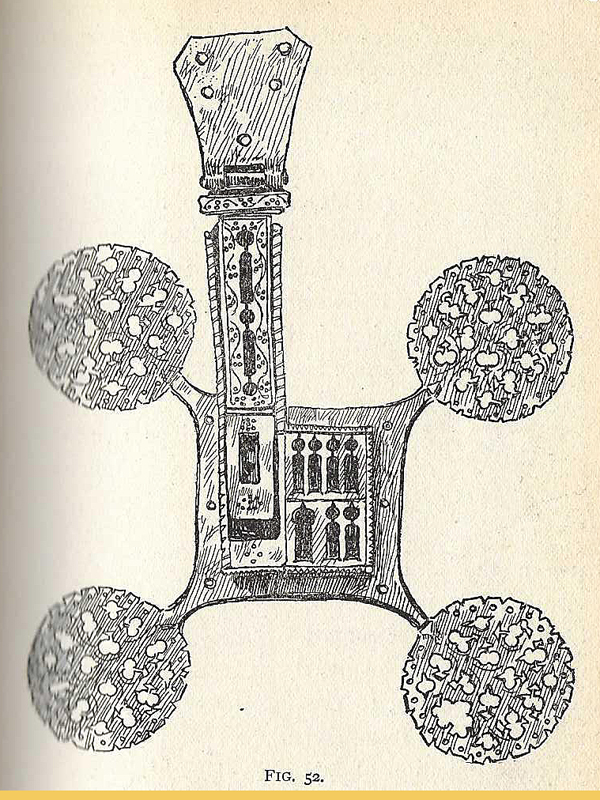

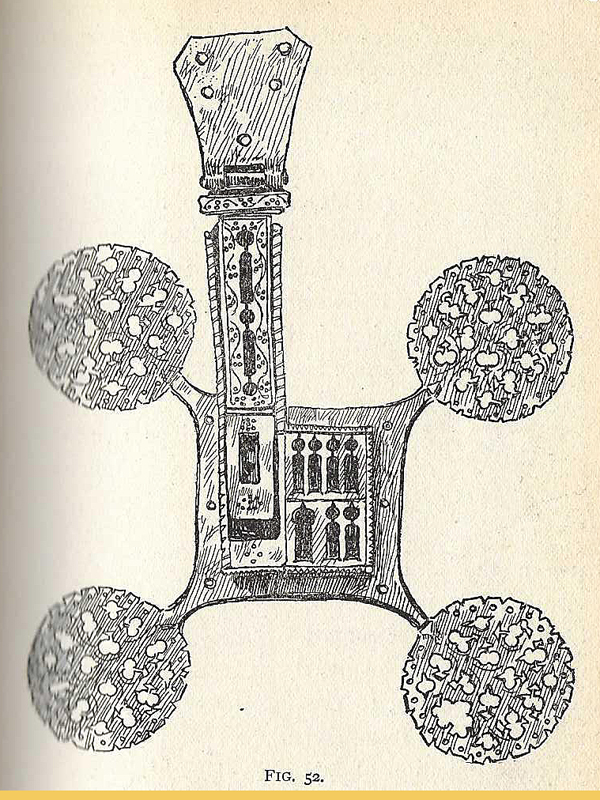

In Figures 52, 53 the tool influence is notable throughout. We may feel sure that the forms of leafage in the early work were first suggested by the iron as it took shape under the hammer rather than from any conscious effort to conventionalize some specific natural form.

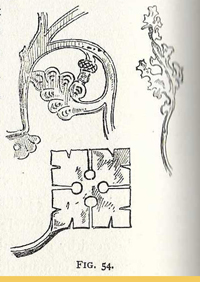

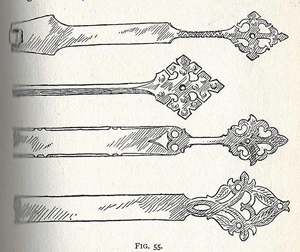

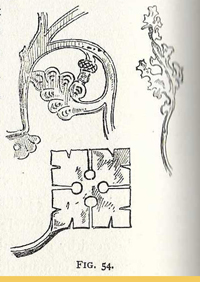

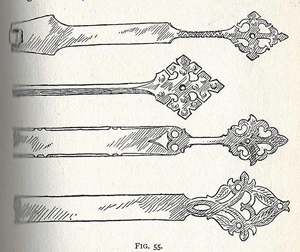

Abstract leaves, as in Figure 54, would inevitably lead to leaves of a more imitative sort. The hinge ends in Figure 55 illustrate the close relation between tool work of a purely abstract character and tool work influenced by observation of Nature. Abstract leaves, as in Figure 54, would inevitably lead to leaves of a more imitative sort. The hinge ends in Figure 55 illustrate the close relation between tool work of a purely abstract character and tool work influenced by observation of Nature.

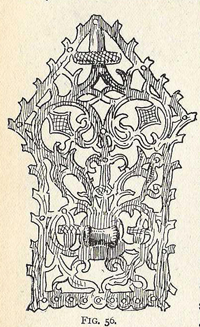

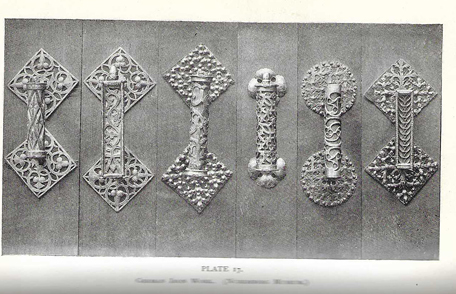

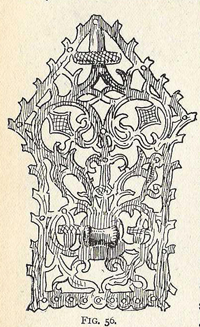

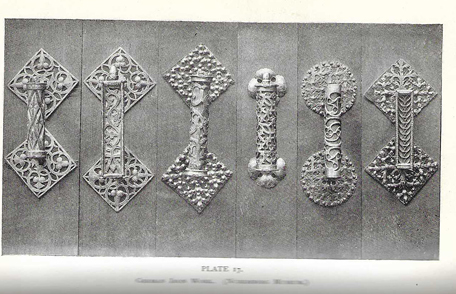

In Figure 56 and in the German door pulls of Plate 17 the refining influence of Nature again appears. For a long time the craftsmen stood at the fascinating borderland between technique and Nature, when it is difficult to say : " This started from the tool ; this from Nature." But even in the most delicately forged and chiseled leaf work we may see how the designer's thought followed closely upon his tools, materials, and processes. In Figure 56 and in the German door pulls of Plate 17 the refining influence of Nature again appears. For a long time the craftsmen stood at the fascinating borderland between technique and Nature, when it is difficult to say : " This started from the tool ; this from Nature." But even in the most delicately forged and chiseled leaf work we may see how the designer's thought followed closely upon his tools, materials, and processes.

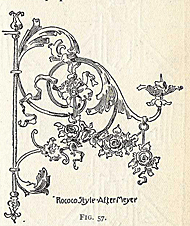

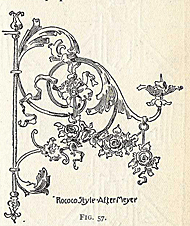

In all these things there is a refreshing vigor, a simplicity, a direct relation and its execution lost in the work of later years. The rugged quality peculiar to iron gives way to finer finish, to elegance of line and form, and to a close imitation of Nature. The turning point is reached when the iron worker subordinates the technique of his craft to imitative work; when he essays the production of such things as may be seen in Figure 57, festooned garlands of roses with flying ribbons. Whatever there may be of grace and elegance in the result, however consummate the skill of the worker, windblown iron ribbons and strings of naturalistic iron flowers are illogical and inconsistent with the material in which they are executed. Then, when we find that touches of paint were added to enhance the naturalistic appearance of the work, we have arrived at the other extreme of the transition. The iron worker began by drawing upon Nature for suggestions that would add beauty to the structural lines of his design, and ended by subordinating his material to a minor plane of illogical imitation. In all these things there is a refreshing vigor, a simplicity, a direct relation and its execution lost in the work of later years. The rugged quality peculiar to iron gives way to finer finish, to elegance of line and form, and to a close imitation of Nature. The turning point is reached when the iron worker subordinates the technique of his craft to imitative work; when he essays the production of such things as may be seen in Figure 57, festooned garlands of roses with flying ribbons. Whatever there may be of grace and elegance in the result, however consummate the skill of the worker, windblown iron ribbons and strings of naturalistic iron flowers are illogical and inconsistent with the material in which they are executed. Then, when we find that touches of paint were added to enhance the naturalistic appearance of the work, we have arrived at the other extreme of the transition. The iron worker began by drawing upon Nature for suggestions that would add beauty to the structural lines of his design, and ended by subordinating his material to a minor plane of illogical imitation.

PROBLEM. In the definition of principles through abstract work it may be noted that three types of problems are available : A figure inclosed on all sides, such as the square ; a figure inclosed on two sides, like the border, but possible of indefinite extension on the two other sides ; a pattern which may be indefinitely extended on all sides, like the surface repeats of this problem. As a constructive arrangement of the elements of design the surface pattern demands persistent effort, close attention to space and mass relations, and the rhythmic connection of details to secure unity. Here, as in the previous problem, nothing could be more stupid than the mere repetition of a " unit," leaving to chance the organic relation of the repeats.

|

![]()

Into the worker's kit there came in due season other tools, such as the drill and file ; and here again we may follow the trail left by these tools through innumerable examples of openwork ornament leading to forms of leafage and intricate traceried patterns. Working on the cold metal was more generally practiced, and the character of the enrichment accordingly underwent a change. The traceried patterns, suggested presumably by the masons, were of rare beauty, often complicated in appearance and of ingenious workmanship (Figure 50).

Into the worker's kit there came in due season other tools, such as the drill and file ; and here again we may follow the trail left by these tools through innumerable examples of openwork ornament leading to forms of leafage and intricate traceried patterns. Working on the cold metal was more generally practiced, and the character of the enrichment accordingly underwent a change. The traceried patterns, suggested presumably by the masons, were of rare beauty, often complicated in appearance and of ingenious workmanship (Figure 50). In Figure 51 is a very abstract sort of leafage, just the thing that a workman with punch and cold chisel would shape from a flat piece of metal ; it is tool-made Nature.

In Figure 51 is a very abstract sort of leafage, just the thing that a workman with punch and cold chisel would shape from a flat piece of metal ; it is tool-made Nature.

Abstract leaves, as in Figure 54, would inevitably lead to leaves of a more imitative sort. The hinge ends in Figure 55 illustrate the close relation between tool work of a purely abstract character and tool work influenced by observation of Nature.

Abstract leaves, as in Figure 54, would inevitably lead to leaves of a more imitative sort. The hinge ends in Figure 55 illustrate the close relation between tool work of a purely abstract character and tool work influenced by observation of Nature.

In Figure 56 and in the German door pulls of Plate 17 the refining influence of Nature again appears. For a long time the craftsmen stood at the fascinating borderland between technique and Nature, when it is difficult to say : " This started from the tool ; this from Nature." But even in the most delicately forged and chiseled leaf work we may see how the designer's thought followed closely upon his tools, materials, and processes.

In Figure 56 and in the German door pulls of Plate 17 the refining influence of Nature again appears. For a long time the craftsmen stood at the fascinating borderland between technique and Nature, when it is difficult to say : " This started from the tool ; this from Nature." But even in the most delicately forged and chiseled leaf work we may see how the designer's thought followed closely upon his tools, materials, and processes.

In all these things there is a refreshing vigor, a simplicity, a direct relation and its execution lost in the work of later years. The rugged quality peculiar to iron gives way to finer finish, to elegance of line and form, and to a close imitation of Nature. The turning point is reached when the iron worker subordinates the technique of his craft to imitative work; when he essays the production of such things as may be seen in Figure 57, festooned garlands of roses with flying ribbons. Whatever there may be of grace and elegance in the result, however consummate the skill of the worker, windblown iron ribbons and strings of naturalistic iron flowers are illogical and inconsistent with the material in which they are executed. Then, when we find that touches of paint were added to enhance the naturalistic appearance of the work, we have arrived at the other extreme of the transition. The iron worker began by drawing upon Nature for suggestions that would add beauty to the structural lines of his design, and ended by subordinating his material to a minor plane of illogical imitation.

In all these things there is a refreshing vigor, a simplicity, a direct relation and its execution lost in the work of later years. The rugged quality peculiar to iron gives way to finer finish, to elegance of line and form, and to a close imitation of Nature. The turning point is reached when the iron worker subordinates the technique of his craft to imitative work; when he essays the production of such things as may be seen in Figure 57, festooned garlands of roses with flying ribbons. Whatever there may be of grace and elegance in the result, however consummate the skill of the worker, windblown iron ribbons and strings of naturalistic iron flowers are illogical and inconsistent with the material in which they are executed. Then, when we find that touches of paint were added to enhance the naturalistic appearance of the work, we have arrived at the other extreme of the transition. The iron worker began by drawing upon Nature for suggestions that would add beauty to the structural lines of his design, and ended by subordinating his material to a minor plane of illogical imitation.